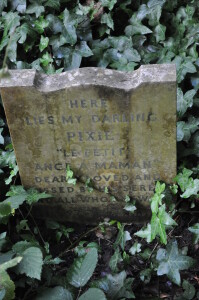

A pet gravestone from Hyde Park (wording below). Credit: Eric Tourigny taken with permission of The Royal Parks

In 1885, an elderly Scottish woman decided to bury her cat, Tom, in a nearby cemetery. Though the decision might not seem controversial to us, it caused a riot in Edinburg.

The woman, hoping for a “decent burial” for Tom, had an undertaker create a casket for the cat and employed a gravedigger to dig the grave. The funeral itself was largely attended.

But that’s also where the problems started. Apparently objecting to the burial of an animal like a human, a crowd amassed and denounced the proceedings. The crowd destroyed the coffin, dug up the cat, and forced the woman to flee from her home.

By the end of the century, however, pet burials had become common, as large pet cemeteries like Hyde Park in London and the Hartsdale Pet Cemetery & Crematory interred hundreds to tens of thousands of dogs, cats, and other animals.

Now, one intrepid scientist has walked the grounds of four of the UK’s largest pet graveyards, taking detailed notes on every gravestone he could. What he’s found won’t surprise anyone who follows this blog: Over the past hundred years, owners have begun to view their pets more like members of the family. As the years went on, pet gravestones were more likely to include the family’s last name, refer to the owner as a parent, and even suggest that the family would meet the pet again in heaven. Here’s one from Hyde Park:

Here Lies My Darling Pixie

Mommy’s Little Angel

Dearly loved and

Missed by his Serena and all who knew him

11.11.1970 – 3. 11. 1976

The changes aren’t surprising, given what I’ve written about our changing relationship with cats and dogs in Citizen Canine. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries–as pet cemeteries were becoming more common–dogs (and eventually cats) began to live indoors in large numbers, thanks to the advent of flea shampoo and kitty litter. Families also grew smaller and more prosperous around this time, giving them more time to dote on their animal companions. And pet food, toys, and medicine became more sophisticated, in some cases rivaling those available to humans. All served to transform dogs and cats from mere companions to bona-fide members of the family. And now, we’re seeing that evolving relationship play out in pet gravestones.

As for poor Tom, his owner would be heartened to learn that, more than 130 years later, burying a pet in a human graveyard had also ceased being verboten. In 2016, New York made it legal for pets to be buried with their owners in human cemeteries. “Four-legged friends are family for many New Yorkers,” the state’s governor, Andrew Cuomo, said at the time. “Who are we to stand in the way if someone’s final wish includes spending eternity with them.”