On September 13, 1899, a dour-looking Manhattan real estate salesman named Henry Bliss stepped off a streetcar near Central Park. As he turned back to the trolley to help his female companion disembark, an electric taxicab struck him. The carriage-like vehicle knocked Bliss to the pavement and ran over his head and body, crushing both. When he died the next morning, he became America’s first pedestrian killed by an automobile.

Bliss’s death signaled a new era for New York. The city’s streets had once been fluid with horses. Hundreds of thousands of the animals towed railroad cars and fire wagons, barges and slaughter carts. The metropolis ran on its horses—and it worked them to death. The animals were so plentiful that it was cheaper to buy new ones than to properly care for them. And so drivers starved them, whipped them bloody, and left them to die on the side of the road when they collapsed. Too heavy to move, their bodies were allowed to rot until they had decomposed enough for wagons (drawn by horses) to pick them up and dump them in the river—or ship them to factories that turned them into glue, grease, and fertilizer. Horses can live for more than 30 years; in mid-nineteenth-century New York, they were lucky to reach their second birthday.

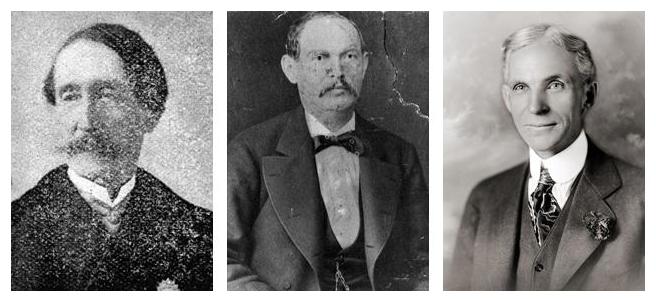

Disgusted with this state of affairs, a privileged Manhattanite named Henry Bergh gathered his high-society friends in 1866 and petitioned the New York state legislature to create the first animal protection organization in the United States. He called it the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Though Bergh was concerned with the plight of all creatures great and small, he focused much of his attention on horses. He lobbied for tough welfare laws that made it a crime to beat or overwork the animals, and he patrolled the streets with fellow members of the ASPCA, scanning for cases of cruelty. Bergh pulled abusive drivers off their wagons, created the first ambulance for injured horses, and caused daylong traffic jams when he ordered passengers to disembark from overloaded streetcars, some holding more than 100 people and pulled by just two horses. Newspapers branded him “The Great Meddler.”

But Bergh eventually won the public’s respect. And he helped create a culture of kindness towards animals the likes of which New York—or America for that matter—had never seen. “Almost every fourth person knows him by sight, and the whisper, ‘That’s Henry Bergh,’ follows him, like a tardy herald, wherever he goes,” read an 1879 article in Scribner’s Monthly. By the time Bergh died in 1888, the ASPCA had prosecuted 120,000 cases of cruelty and inspired 37 of the 38 states to enact strong animal welfare laws, many of which were enforced by local SPCAs modeled after Bergh’s society.

But the clip-clop of the horse eventually gave way to the buzz of the automobile—and no man did more to make this happen than Henry Ford. Cars had been around since the 1880s, but the Michigan industrialist found a faster way to make them. Much faster. Ford’s adoption of the assembly line allowed his factories to assemble a car in less than two hours, and by 1918, half of the autos in the U.S. were Model Ts. Thousands zoomed the streets of New York. Though a Model T didn’t kill Henry Bliss, the car and its kin ended the reign of the horse.

The ASPCA had to move on to new animals. And indeed, by the turn of the century, it had already begun focusing much of its attention on cats and dogs. Both pets had firmly established themselves in the human home, but they had virtually no legal protections until Henry Bergh’s organization came around. The anticruelty laws the ASPCA helped create also applied to cats and dogs, giving them their first true legal protections—the right to be free from pain and suffering.

Dog catchers apparently didn’t get the memo. These rogue agents made their living selling lost dogs and cats back to their owners, and little appears to have dissuaded them from making these pets go “missing” in the first place. Newspapers of the time are replete with tales of dog catchers prowling yards, snatching animals from distracted owners, and even beating people up to steal their pets. When the dog catchers couldn’t sell these animals, they packed them into iron cages and drowned them in the river.

The public was outraged. New York turned to the ASPCA for help. In 1894, the society agreed to take over the city’s animal control duties. It created humane shelters, developed kinder methods of euthanasia, and continued to fight for the welfare of cats and dogs. Since then, thanks to the efforts of the ASPCA and other animal organizations, nearly every state has adopted felony anti-cruelty laws, Congress recently passed an act requiring that the needs of pets be considered during natural disasters, and legislatures across the U.S. are pushing to create animal abuser registries akin to those for sex offenders.

Today, cats and dogs are the most legally protected animals in the country. And it all started with a few guys named Henry.